As urban space has been taken over by regeneration and building work that changes the locality and so the way people engage with it.

Photographs: Changed localities such as the Riverside, the place of the Riverside Museum and the Tall Ship), The Seagull Trust Boathouse, and the Southbank marina also change the way people interact with the environment. Credit: CMT; Author's own.

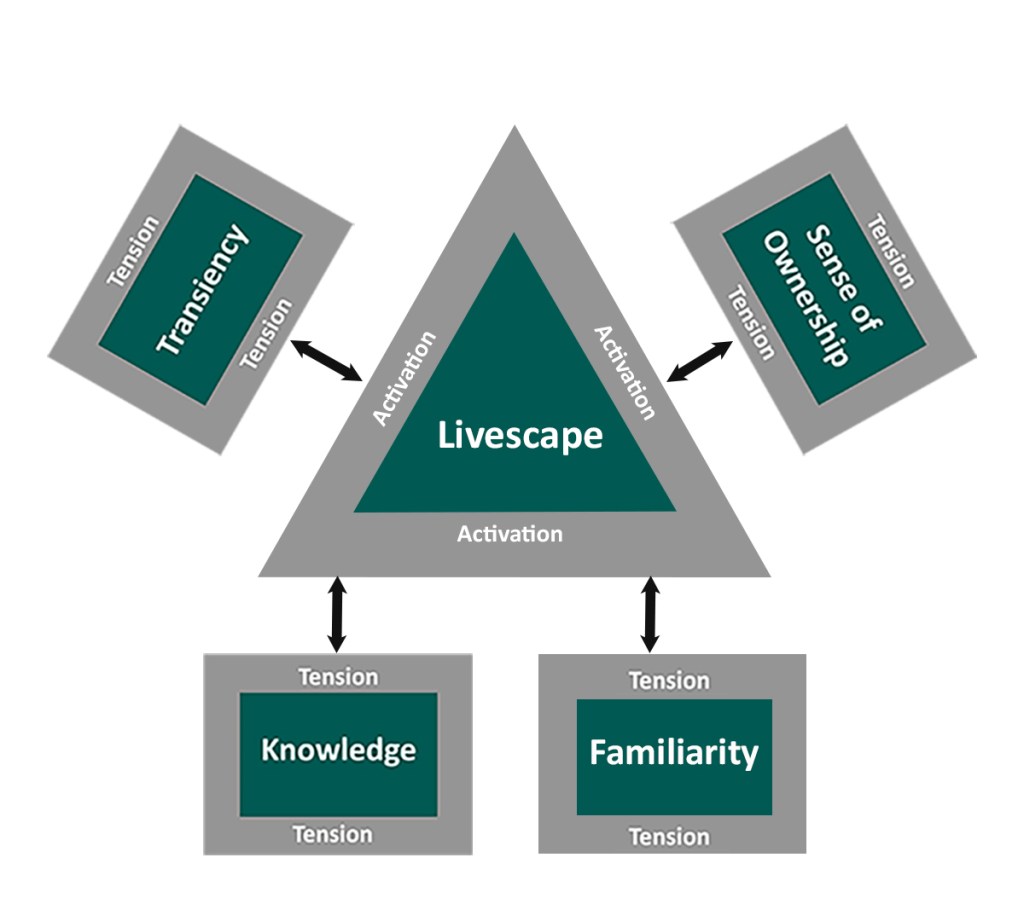

This research suggests a model of engagement with the heritage landscape: the activated livescape. the livescape, when activated, uncovers the tensions that exist in that locality. The research has identified four main tensions in the heritage landscape that affect meaningful engagement: transiency, familiarity, knowledge, and sense of ownership.

Figure 1: The livescape

Diagram: The landscape, when activated by participation, uncovers four tensions that affect meaningful involvement. Transiency in the locality is the experience of the ever-changing environment, through regeneration or through movement (such as immigration). Familiarity in the locality is the opportunity to freely be and act regularly in the landscape, so it becomes familiar (free access to public space). Knowledge in the locality is the one that is not connected with and directed by the structures of power in the urban environment, such as local authorities, heritage institutions, and the government. Sense of ownership comes when familiarity and knowledge allow communities to feel that decisions-making in the locality is shared on equal terms between the ones who occupy it, rather than just witness changes that have been decided by the authorities for their neighborhoods. Credit: Author's own.

Tension 1

The locality of the heritage landscape is ever-changing, either through regeneration or through movement such as migration or displacement.

Photographs: New flats are getting built next to the Riverside. Tow bridge and pontoon, Southbank marina, Kirkintilloch. The development of the river Clyde waterfront, Whiteinch.Credit: Author's own.

New things in the locality such as towbridges and pontoons are part of the characteristics that changed recently in the Forth and Clyde canal since it was re-opened for boats, from sea to sea. The waterfront of the river Clyde changed too, with new buildings such as the Riverside Museum. These changes transformed the locality and the way the connections within it took place. Communities that have difficulty accessing services and in having a saying in decision- making about these changes are in danger of becoming unfamiliar with their locality. If one cannot access the new changes in the locality, one can’t participate. With no participation the ‘being there’ becomes restricted. When people in the Forth and Clyde canal’s locality were asked during the Scoping study about their views on the canal, they felt that in some ways they are not familiar with the waterway.

Photographs:In Kelvin Harbour a new tow bridge is getting buil to connect two communities across the water. In the past the connection was taking place with Ferry No8, now a restored historic vessel moored at the harbour, but not used for its purpose. Credit: Author's own.

Kelvin harbour houses groups and clubs that use small boats to connect local communities with the river. Cultural organisations that took part in the seminar use the harbour for boating activities. In the picture above, the works are shown on the new bridge that will connect the Riverside Museum with Govan. Another tow bridge is planned over the harbour with a leisure complex to be constructed on the field next to it. These new developments to the landscape around the river will possibly affect participation with the harbour and they will cause continuing changes in the locality.

Tension 2

The ever-changing heritage landscape blocks opportunities to get familiar with ‘being there’ in everyday life.

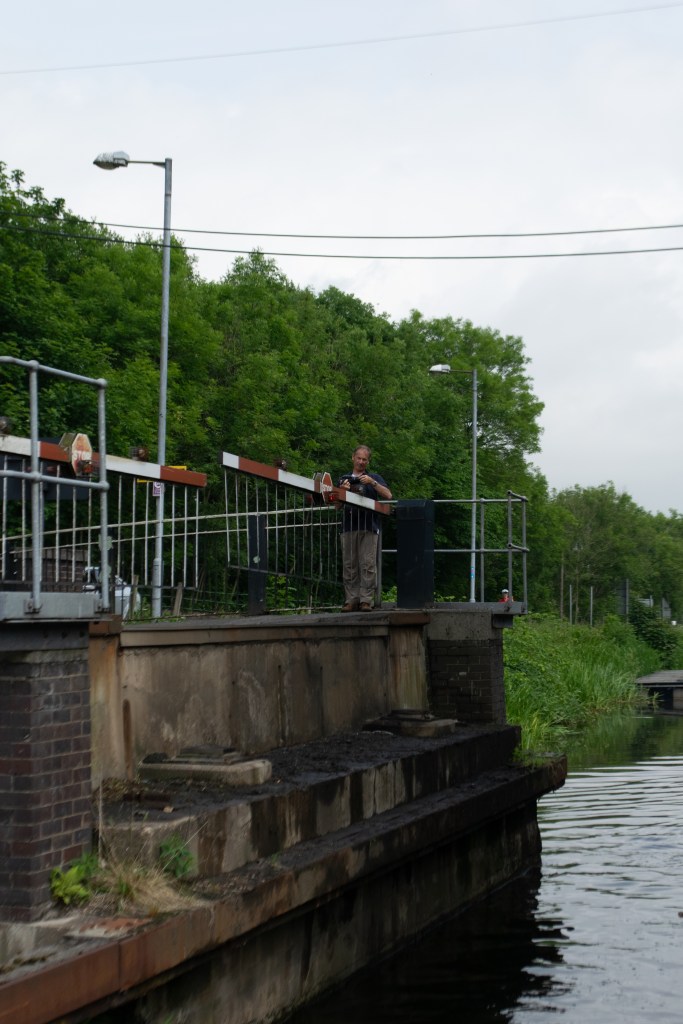

Photographs: Bridge operator. Bridge open on the FCC. Slipway in Kirkintilloch. Features on the canal such as bridges and slipways are essential for access to the waterway. However, bridges need to be operable and they need someone to operate them in order for the boats to go through. Slipways also need to be maintained and have free access to all so communities can enjoy the water with boats. These features are restricted for the general public and access.

In 2018, a set of bridges failed to operate on the FCC so navigation had to stop and parts of the canal were closed. FCCS and other boating groups campaigned for Scottish Canals to find the funds to repair them so the canal could re-open to navigation. Credit: Author's own.

In 2018 there was a rekindling of the campaign to keep the canal open to sea-to-sea navigation, due to the failure of canal bridges to open and let boats through. The Forth and Clyde Canal Society, announced that the closure of the bridges affects boats being on water, and that affects communities’ familiarity with the waterway. They explained that the canal is alive, and when boats do not get through it, vegetation grows which prevents navigation in the future. Scottish Canals, the governing body of all Scottish canals, announced that the failures were caused due to escalating costs of maintenance.

Photograph: Trying out the new boat in the boathouse, boat building workshop, Kirkintilloch.

The young people who built the boat in Kirkintilloch had never been on the FCC, although they grew up with the canal in their neighborhood. During the workshop, which lasted two weeks, they worked in the boathouse and they got used being on the waterway. By the time the boat was finished, they were familiar with the idea of being near and on the water.

Photographs: Participants in the boat-building workshop in Maryhill try one of the boat in the canal.

During the launch in the local canal basin, there was an accident and the bottom of the boat cracked. The boat was floating above a submerged bollard that nobody had noticed. They eventually repaired it and relaunched it successfully at a later date. The incident illustrates how familiarity with the locality has an affect on how communities feel about the place

” Don’t be upset. We now know the ballards are there. We’ll fix this” (Participant 2, Fieldnotes, Maryhill)

Tension 3

Knowledge of a place begins when there is familiarity with the locality. Knowledge belongs to all and all should have equal opportunities to be familiar with their locality.

Photographs: Learning to row the boat they built in Firhill basin. The workshop in the boathouse. Rowing the new boat after the official launch. Author's own.

When the livescape has made heritage active through participation, clashes begin to take shape when gaps in opportunities to participation become obstacles in gaining knowledge. This research suggests that knowing about a place, its past and present, does not depend on the heritage authorities (heritage professionals, local authorities, planners) that hold the power to make changes. On the contrary, knowing depends on the opportunity to take part in the everyday in the locality, without restrictions and gaps in participation. Making the livescape active by connections and interactions with things, animals, people and everything that makes a landscape, even situations such as boating, creates knowledge of a place. When communities have limited access to the decision making in the creation of the locality and the ways they can get familiar with a place, knowing a locality becomes authorized and controlled.

Photographs: Images from the FCCS's campaign to re-open the FCC to throughout navigation. Bbq on a barge with visitors; Canal clean up. Credit: FCCS archive.

The research used parts of oral history interviews with some members of the Forth and Clyde Canal Society. During the interviews it was shown that the volunteers of the Society know the canal very well, and their knowledge comes from over four decades of participating through the campaign in the locality of the canal. The Society has used and maintained boats and perform all sorts of clearing jobs on the canal since the 1980s and they have expert knowledge of the waterway. This compares with the expert knowledge of the authorities that care for the canal (Scottish Canals, local authorities) and who directly decide about the future of it.

“If this Society cease to exist and I’m worried that if we don’t get younger people involved it will eventually, then I’m afraid about the future of the canal. We are the ones that know the canal well and we safeguard that it remains open, through campaigning, through the boats and by always being alert to issues. Sometimes people with authority have no clue of the practical issues that could cause damage.” (Fieldnotes, Member, FCCS, Informal conversation)

Tension 4

Knowing a place, its past and present, and being familiar with it, makes one feel like they belong there and one feels responsible for its future.

Photographs: The FCCS maintains the boats often by slipping them on the bank of the canal. The slipways don't only provide access to the water but they help the boats getting out of it to be repaired. Slipping a boat up a slipway is a skillful job. The FCCS helps other groups and individuals to use the slipway and the the machinery related to it. Credit: Author's own.

The Forth and Clyde Canal Society manages the slipway on the FCC near Kirkintilloch. The slipway is one of the few ones near Glasgow and this is important because it helps connections and participation of local communities with boats. A slipway serves for launching boats and their repairs and maintenance, so it is an important part of the canal. By managing the slipway, the group builds familiarity with the place and it feels responsibility for the canal’s preservation and future. The familiarity and the know-how of a locality encourages the desire to be part of the decision-making.

Photographs: At the Riverside, the slipway is next to the Riverside museum at Kelvin harbour. The images are from the launch of boats that had been built by groups in the locality. Credit: Author's own.

On the river Clyde, sense of ownership of the heritage environment emerges through boat-building and putting the boats on the water.

“ I like the diversity of the work. So from one day to another, you’re rarely doing the same thing, which keeps the job very interesting. And from a community engagement point of view, we take a lot of volunteers from fairly, you know, they can be from fairly disadvantaged backgrounds, you know, people that, for whatever reason, usually aren’t at work that can be for a number of reasons. And it can be very rewarding to build sort of, you know, skills and confidence and self efficacy and these people to sometimes return to work or to further education college and just see their confidence really grow.” (Workshop leader, CMT, Interview extract )